In 2021 I was accepted for a translation fellowship program at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). I subsequently spent just under 6 months in Geneva, where I was trained at the WIPO headquarters in the fine art of translating patent abstracts and patentability reports from Japanese into English.

Three years have passed since I completed the fellowship, so I have had plenty of time to mull over my experiences. There doesn’t seem to be a huge amount of information out there about this program so I thought sharing my experiences might be useful for anyone who is considering applying for it, or who has already been accepted.

In this post I’ll talk about the application procedure and in a following post I will detail what happened when I got to Geneva!

First off, let’s go over some basic questions.

What’s WIPO?

WIPO is an agency of the UN tasked with promoting and protecting intellectual property, which includes things like trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets – and patents.

What’s the PCT Fellowship Program?

PCT stands for Patent Cooperation Treaty, an international treaty on patent law, first agreed in 1970, that now (2025) has 158 contracting states. What this means for inventors is, if you have an invention you want to protect internationally with a patent, you can file a single patent application for all the contracting states, rather than having to file separate applications in different countries.

Every non-English-language patent application that is filed in the PCT system has its abstract (basically a summary of its content) translated into English, and non-French-language abstracts are then translated from the English into French. Patentability reports, which decide whether or not an invention qualifies for a patent, are also translated.

This means there is a huge amount of material that needs translating, but as this is a very specialized task, there are never enough qualified translators. So every year WIPO holds a training program in Geneva for suitable candidates to give them some on-the-job specialized translation training that could lead to a career.

Most fellowships last at least 3 months. In the case of Japanese-to-English translation they are usually 6 months. Participants are given a salary (currently 5,000 Swiss francs a month) during the fellowship that should be enough to cover their expenses while in Geneva, plus paid holidays, health insurance, and their flight is paid for too.

There are other fellowships aside from translation. In the year I was accepted there were also fellowship programs for terminology fellows who are trained in creating a term base, and translation technology fellows who are trained in the use of management systems and machine translation systems. By last year (2024) the program had been expanded to include post-editing fellows for the post-editing of machine translations, and technical specialist fellows who are able to share their technical experiences with PCT translators.

In this article I will focus strictly on my experience – the translation fellowship.

Requirements

For the translation fellowship you will need to be currently studying for or already a graduate of a post-graduate degree program such as a master’s course or a PhD in a relevant field such as “translation, terminology, a related linguistic discipline, or in a technical field provided they have a strong linguistic ability.”

Fellows are also expected to translate into their native language.

The language pairs called for vary from year to year, but Japanese is usually on there. In 2021, the language pairs for the translation fellowship were Chinese to English, Japanese to English, Korean to English, and English to Korean (with a localization focus). In 2024 they were just Japanese to English and Korean to English. However, there were Chinese to English and English to French programs available in 2024 for the new post-editing fellowship.

It also says on the annual call for applications: “Prior experience in technical translation would be considered an advantage but is not a requirement” and this is a key point. You might expect that you would need to have a science or technology background to translate patent-related documents, but your linguistic ability is actually much more important. I’ll write more about that later…

The Application Timeline

The call for applications usually appears on the WIPO news page sometime in late January, but the date varies every year, and in 2021 (perhaps due to the pandemic?) it was as late as February 24. Usually you will have a month’s window to get your application in.

Why I Applied

I first heard about the fellowship program in 2017 when I was studying for a master’s degree in translation studies at Dublin City University (DCU). One day a young man, who was a former WIPO fellow, came in to talk to us about his experience. I’m not show if he would like me bandying his name about online, so let’s call this fellow Bruce (random choice).

Bruce told us about how he had applied for the program and been accepted for it despite having no technical experience. He was then trained by the full-time translators at WIPO who would give him something to translate and then give him feedback. When his translations weren’t judged adequate he would often have to translate the material again.

After the fellowship, Bruce worked as a freelance translator with WIPO as one of his clients. I remember him saying he enjoyed the close level of detail and the attention to accuracy that is required when translating patent documents, which was more preferable to him than something like literary translation that requires a more imaginative or creative approach.

So a number of things struck me about this program.

- First, you get to live in Geneva for a few months, which sounded rather glamorous.

- Next, the pay is pretty good for what is essentially a fancy-pants internship – it was actually just 4,000 Swiss francs then (2017), but still enough to live comfortably in one of the world’s most expensive cities.

- Also, it could be a fast-track into a rather lucrative career. If you want to make a decent living as a translator, then it’s a good idea to develop a specialty. I didn’t have one – maybe translating patent documents could be it? The head of my master’s course also told me that she thought Bruce was getting paid rather well from WIPO…

Patents by their nature contain a lot of technical and scientific information and I didn’t have a scientific or technical background (my background is literature). But Bruce didn’t either – and look at him now! I resolved to give it a go.

Three Times Lucky

To apply for the fellowship program you first need to send in a resume and a letter of motivation stating why you are interested in taking part. If the folks at WIPO like what they see, you will then be invited to take a test. My experience is probably a little unusual in that I actually applied for this program and took the test three times before I was finally accepted. Needless to say, passing that test proved to be quite a challenge. Here’s what happened.

My First Application – 2018

When the call for applications came out in January 2018, I spent many long hours working on my application. Back in November, we’d had a visitor from WIPO at DCU, a senior terminologist, who came to talk to us about terminology (part of our course). Someone had asked him what WIPO looked for in applications for the fellowship program and he had answered: passion.

So I was very keen to show my sincere interest in translating patent-related documents, despite having never considered it previously. I figured I needed some advice for my application so I asked a career consultant at the university for her help. We met multiple times and she gave me heaps of help and heavily edited and polished my first drafts until they were as perfect as they could be. I tried to highlight any technical translation experience I had (which wasn’t a lot) and those aspects of my master’s course that I thought were relevant.

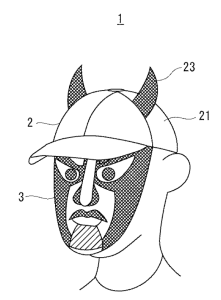

As I recall, I received an invitation to take the test sometime in March. People were congratulating me for simply getting to that stage of the process, so I guess not everyone does get that far. The test itself seemed pretty straightforward and oddly not that difficult. It was just one translation exercise based on this patent for a “transformation cap” and came it with this illustration (which actually made me laugh out loud):

If I remember correctly, I also had to provide suitable descriptions for the numbered parts on the illustration. Like I say, the test itself didn’t seem that difficult, but it was still rather never-wracking because there was a strict time limit and also this instruction: “Once you have started, do not close the browser window or leave the test page,” which meant if there was a power cut or I accidentally shut the page, the test would automatically be over. I should add at this point that the test is no longer done this way (or it wasn’t the last time I took it).

Anyway, I felt I had done my best and waited patiently for the results while preparing myself for a possible interview. But one day in April (Friday the 13th as it happens) while I was taking a class at DCU I received the fateful email that I would not be invited to an interview.

My Second Application – 2020

When you receive that rejection email from WIPO they don’t tell you what you did wrong on the test, only that “the program has generated much interest”. It bugged me that the test had seemed so easy, but I still hadn’t passed it.

Meanwhile, two friends of mine on my master’s course were accepted for terminology fellowships. I didn’t resent them getting accepted – they totally deserved it. But I couldn’t help imagining how much fun it would have been if the three of us had gone to Geneva together.

It occurred to me there must be something special WIPO looks for in a patent translation, something in the phrasing or the sentence structure… So I kept thinking about that test, and I thought – if I can spend some time studying patent translation and figure out what makes it different, maybe I can take that test again.

I found an online translation course which was reasonably priced and you could work through it at your own pace. Called the “Kanji Foundry”, it’s sadly no longer available, but I thought it was pretty good. Each lesson would introduce one of the common words, phrases or constructs often found in patents, with example sentences and translation exercises. As I worked my way through it, I gradually got used to the typical language and language patterns of patentese and by the time I’d finished, I felt ready to take that WIPO test again.

I should mention that the Kanji Foundry course was aimed at people with a background in medicine, pharmaceuticals, or biotechnology, which I don’t have at all. But I took my time over it, looking up technical terms in those fields as I went along, and somewhere along the way, I began to find those fields very interesting.

Meanwhile, I’d also boosted my CV by taking some other online courses, which included an introductory course in Biochemistry and a General Course in Intellectual Property from WIPO’s e-learning center.

So I reapplied in mid-February 2020, and in early March I was invited to take another test. The form of the test had changed, however. This time there were three sections: two passages to translate and a terminology research question. And they all had to be completed within the 4-hour time limit.

The first section was focused on English writing ability. My task was to translate the Japanese into “idiomatic English” (by which they meant natural English) “that clearly and accurately” conveyed the Japanese meaning. No problem.

The second section was focused on the ability “to parse and comprehend technical passages containing complex grammar” and to produce a translation that was “clear, concise and accurate.” Maybe I couldn’t have handled that complex grammar back in 2018, but thanks to my online studies, I felt I managed this ok.

Note that the content in these first two sections was more serious than that of 2018, being about a device for generating sign language computer graphics in section 1, and a device for expanding parachutes in section 2.

The third section, terminological research, totally threw me. I had to find the English equivalents for two Japanese terms, provide a brief explanation of their meaning in English in my my own words, and cite up to three sources to support my conclusions. I simply couldn’t find them. To this day I have no idea what the English equivalent of ドッグ当たり is.

Naturally, I was crushed. After all my preparation, I’d been thrown by a completely unexpected question. It occurs to me now, that if I had taken a test like that in 2018, I probably would have accepted that I wasn’t cut out for that kind of work and wouldn’t have tried again. But in 2020, I felt like I had come very close… I just needed to work on my terminology research skills. I resolved to try again.

My Third Application – 2021

I have no idea why WIPO PCT started including such difficult terminology research questions in their fellowship tests. When I actually did my fellowship, I found terminology to be one of the easiest parts of the job – and I don’t think I ever had to find anything as difficult as they put in their tests. I can only assume the tests are designed to be so hard that only the most superlative candidates can make it through. The fact is the number of places available for these fellowships are very limited, because the people who do the training also have other duties and they have a limited amount of time to devote to teaching. So only two or at most three people can be accepted in any given year.

So in 2021, I knew I needed to be ready for that terminology question. But how to prepare? Well, I knew two people who had completed WIPO’s terminology fellowship, so I asked their advice. I also asked the advice of one of my teachers at DCU who had taught the terminology course. One friend in particular was very helpful as she told me how she would have approached such an exercise.

In the intervening year, and to show I was still really keen, I boosted my application with yet more online courses, which included:

- Searching Prior Art Based on Patent Applications, from the European Patent Academy

- Google IT Support Professional Certificate, from Google

- Clinical Terminology from the University of Pittsburgh

- Advanced Course on Basics of Patent Drafting, from WIPO

- e-Tutorial on Using Patent Information, from WIPO

I have no idea if any of those courses were really necessary, but as I said, I wanted to show I was keen, and it seemed to work, because in late April 2021 I was invited to take another test.

This time, the test had a very generous 12-hour time limit, although I think they said I should be able to finish all the materials in three hours. There was just one translation exercise this time, albeit a relatively lengthy one (based on this), and there was just one term that I had to find an equivalent for (二極スパッタ法 – see if you can find it). I finished both questions well within the time limit, and even had time to go for a stroll to clear my mind half way through.

I think I took that test on May 2, and I received a friendly email from the head of the Asian Languages section at WIPO PCT, inviting me to an interview on May 18. I was punching the air with joy.

I was asked to review my test before the interview and to look for “anything you may have translated differently the next time”. The interview was held about a week later, over Zoom, and with all five of the Japanese-English revisers at WIPO PCT as well as the lady who had sent me that email invitation. Everyone was very cheerful and friendly during the interview and made a good impression on me. I was a little worried before the interview that it might be held in Japanese, but they were all native English speakers and like me, most comfortable in their own languages, so I needn’t have worried.

On June 9, I received an email telling me that they were going recommend me for the fellowship. My candidacy was then passed around a variety of desks for a few months (my first taste of WIPO bureaucracy) – and was finally fully approved on August 6. My contract was scheduled to start on September 15. I was going to Geneva.

The Takeaway

Nobody likes to fail or be rejected. I obviously don’t – hence my persistence. But if you do take the test for this fellowship, and you don’t pass, you really shouldn’t take it to hard. Clearly, the test is designed to be extremely difficult to pass. But another point to consider is that due to the limited number of places, they really do need to narrow down the field of candidates to just a few people, which means you could well have failed by a whisker.

If you do decide to apply for the fellowship and take the test, remember that not only the content but the form and the length of the test changes radically every year – so be prepared for the unexpected. And if I had any tips to give for terminology research questions, it would be simply this: Google Patents is a good place to look first.